Q, Trust, and You

We all rely on unverified testimony. QAnon happens when you trust the wrong people.

The QAnon conspiracy narrative is built from absolutely insane pieces and lots of people believe in it. I knew that already. But it hits differently when you see it. Watching the first episodes of Q: Into the Storm on HBO and its depiction of totally ordinary, familiar white folks scrolling through their Costco iPads on their Costco sofas spouting bonkers claims, I found myself agog with incredulity. It didn’t matter that their comprehensive enmeshment in this demented, ad hoc revenge fantasia wasn’t actually news to me. It’s sort of like the Grand Canyon. You always knew it was there and enormous. Nevertheless, stunning to see.

I kept thinking: “These people don’t even know what evidence is…”

It’s not as if Qanon devotees are trying to determine the plausibility of the conspiracy’s constituent propositions against some standard of logical consistency or coherence with their pre-existing beliefs. They aren’t doing this badly. They aren’t doing this at all. They read stuff on 8chan and watch videos on YouTube and just believe it. Insofar as there’s any impulse to maintain a web of personal belief that isn’t a chaotic jumble of internal contradiction, they do it by regarding Q’s revelations, and the interpretation thereof by an emergent class exegetical elites, as their fixed points. Everything that conflicts with them, they drop or revise, even if those beliefs were much better grounded in reason and reality. It’s wild!

I was launched back into this bewildered amazement by Laura Nelson’s fascinating piece about QAnon and SoCal woo in the LA Times.

We get treats like this:

When the world shut down in March of 2020, Eva Kohn of San Clemente created a group text to stay in touch with nine other women in the area. Niceties about families and lockdown hobbies devolved over the months into false conspiracy theories: that Democratic elites were harvesting adrenochrome from tortured children to use in satanic rites, that the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol was perpetrated by antifa, that the COVID-19 vaccine causes infertility.

People believe this! Lots of people! Now, I doubt that you're very surprised to find that folks who will believe in chakras and auras and manifesting things into reality by, like, thinking about them really hard might also believe that Hillary Clinton devours baby faces or whatever. Still, it’s a bracing reminder of the suggestible wildness of the human mind.

Anyone this epistemically dissipated — anyone this anarchic and antinomian about norms of truth-conducive cognition — can end up believing anything. It’s astonishing to see people fervently believing any old arbitrary thing in a massively coordinated way.

Or maybe not so astonishing. If you know where to look, you can see it every Sunday morning. Maybe it’s not so different from what we all do, in a way.

This bit sparked a thought:

“People aren’t taking QAnon as seriously as they should, given how pervasive it is in these worlds — evangelical Christians, yogis — that otherwise have very little in common,” Schwartz said. “They’re creating a world where truth is whatever you feel like it is.”

It’s that last sentence that got to me. I’ve always found the idea that you can just decide to believe something sort of crazy. For a minute I thought maybe the prevalence of QAnon might be a datapoint that counts in favor of “doxastic voluntarism,” as the philosophers call it. I thought maybe I should reconsider.

But this isn’t a story about individuals who independently want to believe that the Pfizer vax will render your gonads moot, and then proceed to will themselves, one at a time, into believing it. This is mass delusion. That makes it seem less than entirely voluntary. People are getting swept up in QAnon for psychologically normal (though no less troubling) reasons. They’re not just deciding to believe in all this. If an individual were to voice belief in this stuff entirely of his own initiative and on his own steam, we’d suspect a loose connection in the noggin. But we don’t think it’s crazy to believe absolutely batshit stuff as long as enough people believe it. Why is that?

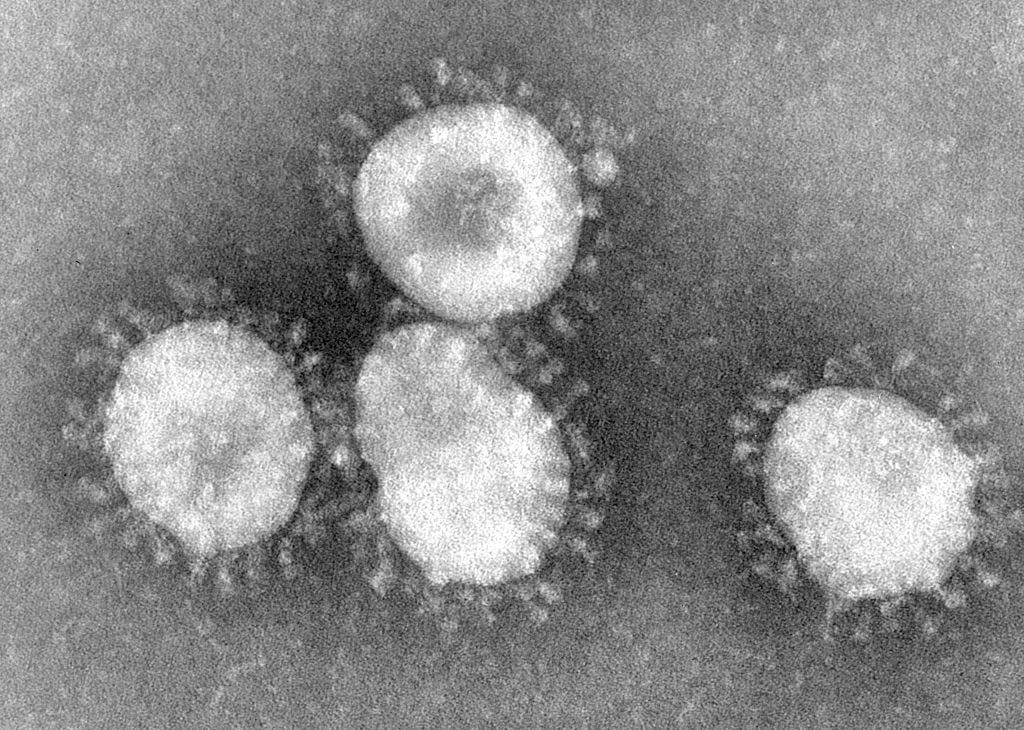

I think it’s because we have no choice but to rely on testimony. I’ve never been eye-to-eye with a virus. I think I’ve seen pictures taken through powerful microscopes. I just take it for granted that these microscopes exist, that they’re powerful enough to take snaps of viruses, and that these alleged depictions are what they’re said to be.

It’s trust. I don’t suspect that any of the people involved in the chain of transmission here are making mischief or telling fibs. The idea that there’s a conspiracy to make me falsely believe that there are pictures of viruses does not jibe with my web of belief. So I don’t give it a second thought. I just assume James Madison was real. All the books say so.

The fact is, almost all the general information in your personal web of belief is stuff you read, stuff somebody told you, stuff you saw on TV. Building a relatively accurate mental model of the world doesn’t have all that much to do with your individual reasoning capacity. It’s mostly about trusting and distrusting the right people. The problem is that few of us have the capacity to independently assess whether someone, or some institution, or some process, is a reliable source of accurate information. You have to depend on other people to tell you whose testimony you ought to trust. There’s no way around it. The bootstrapping problem here is central the human condition. We can’t get started building a model of the world that encompasses more than our own extremely narrow idiosyncratic experience unless, at some point, we simply take somebody’s word for it.

It’s easy to see how, if you start out trusting to wrong people, you can get trapped in a bubble. If you start out trusting the wrong people, they’ll tell you to trust other unreliable people, who in turn will tell you to trust unreliable methods. Worse, they’ll tell you to distrust the trustworthy people spreading the word about the genuinely illuminating results of reliable knowledge-gathering methods. You won’t be listening to the people you ought to be listening to. It’s a problem that comes for most of us, sooner or later. That’s why ideology tends to be self-insulating; it functions as a heuristic for grading the trustworthiness of testimony.

It took me for what feels like forever to finally let go of my ideological libertarianism because I had a hard time extending merited epistemic authority to critics of libertarianism because I’d already extended unmerited epistemic authority to critics of those critics. It didn’t really matter that I was way better at reasoning and evaluating the quality of arguments than most people, thanks to eleventy years of philosophy school.

This side of geometry, just about any serious dispute will turn on a number of empirical assumptions or claims. In sophisticated ideological disputation, confirmation bias takes the form of giving the testimony of some authorities slightly more weight than others, of harboring slightly more concern about the credibility of empirical methods behind inconvenient claims and slightly less about methods that tend to bolster your position. That’s why debates almost never move anyone off their position.

It might even be a little misleading to characterize this as confirmation bias, insofar as that suggests illicitly motivated reasoning. Part of what it means to have a coherent worldview is that your substantive opinions and your views about the reliability of various method of inquiry, experts, and other sources of information are mutually supporting — are in reflective equilibrium.

It’s hard to break out of a stable equilibrium. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be stable. But once you do break out of it, all that is solid melts into air. You rub your eyes and suddenly it’s clear that people you had trusted, who you’d relied upon, were actually full of it. You’re confronted with the fact that you’d been discounting the testimony of extremely trustworthy and reliable people — that you should have been feeling the weight of what they were saying, but weren’t. Even a little reweighting of the relative credibility of expert testimony and various empirical methods can have profound ramifying implications that rock your web of belief.

Now, I’ve come to think that people who really care about getting things right are a bit misguided when they focus on methods of rational cognition. I’m thinking of the so-called “rationalist” community here. If you want an unusually high-fidelity mental model of the world, the main thing isn’t probability theory or an encyclopedic knowledge of the heuristics and biases that so often make our reasoning go wrong. It’s learning who to trust. That’s really all there is to it. That’s the ballgame.

But that’s a lot easier said than done. I can’t use my expertise in macroeconomics to identify which macroeconomists we ought to trust most, because I have no expertise in macroeconomics. I’m going to have to rely on people who understand the subject better than I do to tell me who to trust. But then who do I trust to tell me who to trust?

It’s really not so hard. In any field, there are a bunch of people at the top of the game who garner near-universal deference. Trusting those people is an excellent default. On any subject, you ought to trust the people who have the most training and spend the most time thinking about that subject, especially those who are especially well-regarded by the rest of these people. This suggests a useful litmus test for the reliability of generalists who professionally sort wheat from chaff and present themselves as experts in expert identification — people like Malcolm Gladwell or, say, me. Do they usually hew close to the consensus view of a field’s leading, most authoritative figures? That may be boring, but it’s a good sign that you can count on them when they talk about subjects you know less well.

If they seem to have a taste for mavericks, idiosyncratic bomb-throwers, and thorns in the side of the establishment, it ought to count against them. That’s a sign of ideologues, provocateurs, and book-sale/click maximizers. Beyond prudent conservative alignment with consensus, expert identification is a “humanistic” endeavor, a “soft skill.” A solid STEM education isn’t going to help you and “critical thinking” classes will help less than you’d think. It’s about developing a bullshit detector — a second sense for the subtle sophistry of superficially impressive people on the make. Collecting people who are especially good at identifying trustworthiness and then investing your trust in them is our best bet for generally being right about things.

Model citizens with responsibly sound mental models don’t need to be especially good at independently reasoning or evaluating evidence. They just need to piggyback off people who are. But I digress… sort of.

What’s gone wrong with QAnons is not, as I thought while watching that HBO QAnon doc, that they don’t even know what evidence is, because they do. Testimony is evidence. It’s usually all the evidence we ever get. It’s the basis for most of our perfectly sound, totally justified factual beliefs about the big old external world. What’s gone wrong with QAnons is that they came to trust people who trapped them inside a self-serving hallucination.

Evangelical Christianity teaches people to trust their feelings and the pastoral charisma of hucksters out to get ahead by validating their prejudices — not so different from Marianne Williamson California guru woo. Over time, this became the default epistemology of the American right. Meanwhile, Conservatism Inc. has for decades cultivated distrust in our most reliable and authoritative sources of accurate information — academics, the New York Times, etc. — in an effort to keep their base unified around and agitated by a polarized, highly mobilizing worldview that is, at best, tenuously related to reality. This propaganda shaped and reinforced the political and cultural assumptions of white evangelicals, which worked their way into the content of their weird syncretic Christianity thanks to the grifty, emotive, self-indulgence of their increasingly fused religious/political culture.

All this, together with super-heated negative polarization, readied them to find something captivating and compelling about Donald Trump’s one dumb narcissistic trick of sowing contemptuous distrust in any source of information at odds with his personal interests. The normal follow-the-leader dynamics of partisan opinion-making made it easy for Trump to shut down the influence of anyone or anything telling the truth about Trump. Most of the right’s remaining tethers to reality were left flapping in the wind.

Membership in a community that confers status and trust on people worth trusting about the way things are supplies what you might call epistemic herd immunity. We mostly believe what people like us believe just because they believe it. And that’s fine, as long as the community’s beliefs are ultimately based on trust in genuinely trustworthy people. Under the influence of footloose evangelical epistemology, decades of partisan propaganda and disinformation and, finally, Trump’s “it’s only true if I say it’s true” cult-leader authoritarianism, the American right ceased being that sort of community. It became collectively immunocompromised, susceptible to the rapid transmission of epistemic contagion. It was easy enough for QAnon to win trust and burrow into its hosts by latching onto polarized tribal fidelity to Trump and the cover-up conspiracy theories about Democrats and the Deep State he’d already implanted in his followers to inoculate them against the ugly truth. Once inside the partisan hivemind with root-level permissions, QAnon was able to nuke the remaining exits to reality, achieve full epistemic closure, and trap many thousands in a nightmare dreamscape wholly unmoored from the world.

I don’t care how smart you think you are. It’s dangerous out there, especially if you have an Internet connection. Be careful who you trust. Tune that bullshit detector. Eschew iconoclasts and ideologues. Agree with the respectable consensus. Be a model citizen. And if you get a chance, stick up for maligned yet generally reliable sources of information. Stick up for your local critical race theorist. Stick up for the New York Times. If those suggestions make you stiffen, consider the possibility that you have trust issues.

Because I work in an area (litigation) populated with paid and hired experts with varying levels of credibility I would add that any kind of bullshit detector should incorporate coherent understanding of the speaker's motivations. Living an a world of increasingly targeted advertising, I default to the assumption that most people calling, emailing or popping up in my feed are trying to sell me something, and that it is unlikely to be something I want or need. It's not always true, but a decent first position.

Industry analysts are offering plausible arguments to protect their industry. Grant applicants are are protecting their future grants and talking up their interesting but not too out there research. The exception to the rule to trust top experts is that there are lots niche topics where the leading experts are captured or biased by the dynamics of their field, and outsiders really can identify things they are missing.

There is some kind of minimal rationality bar (Occam's Razor?) that these critiques need to pass, and I don't know that I have a more precise way to articulate the difference between Nate Silver posing questions about epidemiology and a random conspiracy theorist than to say that when they show their work one is vastly more persuasive to me than the other.

I thoroughly enjoyed this piece, but I want to flag two additional challenges to Wilkinson's prescriptions:

1. If you try to adhere to the consensus of most disciplines you will be right a substantial majority of the time. But you also guarantee that you'll be wrong a certain fraction of the time, because consensus does sometimes go through a revolution. And these occasional revolutions provide ammunition for those who make sweeping declarations about the fallibility of experts. In a nutshell, every crank arguing for a dissenting position claims his or her theory is the next heliocentrism or plate tectonics.

2. It can be hard for people to determine the consensus position of a discipline. I think climate change is a good example of this. There exists an entire industry of faux-experts intended to shatter the notion of consensus. In some cases, the experts have genuine credentials, publications, and academic standing. They are just outliers. Convincing people not only to trust the experts, but to remain skeptical of experts deviating from the consensus, is a true challenge.