As I was hammering away on the second installment of my absurdly close reading of a Bari Weiss’ column (still coming, don’t worry … or do), I got to wondering why it is that, in a column ostensibly about pushing back against the woke left, she devotes so much space to attacking imaginary disdain for America. That got me asking why it is that affronted defensiveness about American greatness plays such a central role in conservative anti-wokeness generally.

Why do folks get so worked up by the possibility that knocking Robert E. Lee off a plinth will send us careening down a slippery slope that bottoms out with somebody taking Abraham Lincoln’s name off an elementary? Why is it so bothersome to admit that there are shameful chapters of cruel injustice in our nation’s history? Why is it so hard to simply accept that the historical record and publicly available comparative evidence suggests that the United States of America is pretty great in a lot of ways and really awful in a lot of ways?

Well, one of the defining features of the conservative personality is discomfort with ambiguity. “America is pretty great in a lot of ways and really awful in a lot of ways” ought to be uncontroversially true, but it’s the sort of conclusion conservatives find it hard to stomach. There’s a strong felt need to resolve this sort of gray ambiguity into black or white. Because instinctive pride in one’s group memberships — a tendency toward strong in-group bias — is another core feature of the conservative personality, temperamental conservatives will tend to resolve “America’s sort of good and sort of bad” into “America’s really great and probably — no, definitely — the best.”

But that doesn’t make the empirical case for a complicated mixed assessment of your country’s merits go away. The evidence is still out there. Indeed, annoying people just won’t shut the fuck up about America’s dark and/or comparatively underwhelming side. Therefore, to maintain a relatively uncomplicated, positive, exceptionalist outlook, you’ll need to find a way to reject that evidence and dismiss the criticism. So, how do you do that? You blame it on the out-group, of course.

The easiest way to dispense with evidence that your country sort of sucks is to deny that it is evidence. And the easiest way to do that is to attack the credibility and motives of those who set forth unwelcome messages. The foaming right-wing reaction to the 1619 Project is a great example of this. Let’s think about it for a minute.

There’s plenty to argue with in some of the essays and articles that make up 1619 Project, especially Hannah Nikole-Jones’ admitted overstatement of the extent to which the American Revolution was motivated by the desire to protect American slavery. That said, the broader story told by the 1619 Project is pretty close to the consensus view of contemporary academic American historians. Conservatives can’t stand this story. It shows us that nearly every American institution and pattern of social, political or cultural life has been structured (or disfigured) by white supremacy, enslavement, racial apartheid, and systemic discrimination.

Politically, this implies that there’s a great deal of persistent injustice that remains to be rectified, which conservatives find aggravating and objectionable. But I think this is less important than the fact that the actual history of this country can be unpleasant to think about. It’s a story that makes it difficult to sustain unambiguously positive feelings about America’s past or present. But that’s genuinely hard to take when upbeat sentiments about America have been drilled into you since early childhood, your culture tells you that you’re right to feel proud of feeling nothing but proud of your country, and that it’s shameful and disloyal if you don’t.

I think it’s easy to underestimate the power of these sorts of feeling. Let me use myself as an inglorious example.

I was a teenage anti-PC patriot

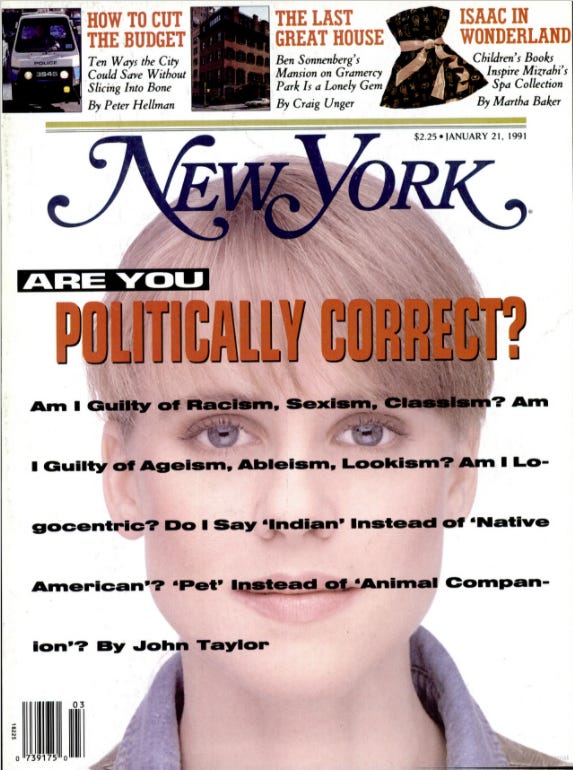

When I first encountered serious academic American history in college, I found it “PC” and really irritating. Back then, in the early-to-mid 1990s, “wokeness” was called “political correctness.” It was exactly the same thing and the panic around it was practically identical.

I was an occasional Rush Limbaugh listener firmly opposed to the “PC thought police, and “feminazis,” too. It just seemed like sound common sense! I was a moderately conservative white guy who grew up in a moderately conservative family in a moderately conservative, overwhelmingly white town. I canvassed for Pat Robertson in the run-up to 1988 Iowa caucus, because my best friend’s evangelical step-dad was a volunteer for the campaign. Personally, I was a Jack Kemp/Pete DuPont man, which is to say, a Republican free-market enthusiast.

In the world I was raised in, a reflexive Cold War-era rah, rah, USA! USA! We’re number one! patriotic spirit was ingrained, universal and felt good to express, especially in crowds. Sure, there’d been slavery, but Martin Luther King, Jr. had solved racism and it was hard to imagine why anybody would spend their time writing about how bad America really was unless they were professional America-haters paid by the Reds to turn good patriots against their country. Nobody had to teach me to think and feel this way. I just absorbed it because it was everywhere.

Please review “America: Fuck Yeah!” below. This is what it looks like when two libertarian-ish Gen-X white guys, just a bit older than me, wallow in the nihilistic joy that their formative Reagan-era jingoism brings to them while sort-of-but-not-really distancing themselves from it by presenting it as scathing satire of Dubya-era war-on-terror jingoism which, in the end, they endorse. I can think of no purer encapsulation of the trashy, self-indulgent nationalist relativism (nationalism is always and everywhere self-indulgent relativism) that white dudes of my generation struggle to let go of. You need something you can pretend you’re only ironically proud of when your soul is otherwise a sucking void of violent resentments and stale pop culture references…

(It’s filthy, so the video isn’t embeddable. Click the picture to watch it at Youtube.)

Anyway, Matt Stone and Trey Parker originate from the same set of cultural coordinates I do. And I distinctly recall feeling frustrated and annoyed about having to read about the middle passage, slave markets, the trail of tears and so forth. It’s not like I’d been assigned Howard Zinn or anything. It was just standard American History 101 stuff and it was packaged more meekly and apologetically than it usually is today. Still, I really didn’t like the way it made me feel.

But here’s the thing: I don’t have a conservative personality. Quite the opposite. I peg the meter on “Openness to Experience” (I’d bet Parker and Stone do, too), a personality trait that inclines you toward liberal views on social and cultural issues. It also makes you intensely intellectually curious, cool with ambiguity and relatively tolerant of the low-grade bafflement and anxiety you get when you venture well outside your comfort zone. So learning about slave markets didn’t make me snap shut like a clam. Learning a little real history made me want to learn more. Still, I was irritated. Nobody likes irritation.

When I was cast at nineteen as the one white guy in the University of Northern Iowa theater department’s production of the August Wilson play “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone,” I only felt a little uncomfortable. Mostly I was delighted to be thrown into a strange-to-me African American group of theater people working together to tell a heartbreaking story about the African American experience. During the first week of rehearsals, when the “radical” black feminist director taught us about the history behind the play, much of it horrifying, I felt some genuine cognitive/emotional dissonance. However, because I am the sort of person who chooses to major in art and tries out for plays, I found this stimulating, too. I didn’t feel that motivated to make the uneasiness go away.

But I did try to make the uneasiness go away. It’s just that, for me, that meant seeking out even more information to see if our director had been exaggerating or cherry-picking facts. (She hadn’t been.) And for a good while after the play had closed I kept my mind busy finding fresh ways to affirm my opposition to affirmative action, to shore up my Charles Murray-ish view that public assistance breeds dependency, and to reassure myself that it isn’t racist in the least to think so. I read Thomas Sowell and Walter Williams books for comfort.

The point here isn’t that I’m good for being open-minded or bad for having sought to rationalize my pre-existing opinions when they were put under pressure by new information. The point is that I am, by temperament, open to new things, tolerant of racial and cultural difference and comfortable with ambiguity. Yet I nevertheless resisted many of the implications of what I was learning — including the implications of the emotional reality of the story I was helping to bring to life on stage — because those lessons didn’t mesh neatly with my Gen X white dude enculturation or my emerging libertarian politics. It took at least another 20 years, and repeated exposure to the same and similar information, for the reality and meaning of it all to really sink in.

If it’s this hard for a white guy with an intensely liberal disposition to resolve, in the direction of truth, the tensions between the actual, easy-to-confirm facts of American history and his conservative “America: Fuck Yeah!” cultural conditioning, then just imagine what it must be like to encounter the same stuff for a white guy with a similarly conservative upbringing and a thoroughly conservative personality. If ethnic and cultural differences make you uneasy, ambiguity makes you anxious, and unwelcome information sparks defensive resistance rather than wary curiosity, getting straight with the actual story of your country isn’t going to take 20 years. It’s just never going to happen. You’re certainly not going to end up chewing on the experience of doing an August Wilson play for decades, because you definitely never auditioned. You’re not going to keep returning to a subject that make you uncomfortable until, finally, it changes you.

I didn’t mean to dwell on this for so long. I just wanted to make it as clear as I can that the “You can’t handle the truth!” explanation for conservative hostility to unflattering stories about American history is more than glib, psychologizing ad hominem. The impulses at work here are powerful. I know it not just because the psychology literature tells me so, but because I’m a human who has, like every human, experienced first-hand how my mind generates resistance to information that threatens my political and cultural identity. The fact that these impulses got in my way for so long, despite the fact that they’re relatively weak in me, has helped me to see how powerful they really are.

Ambiguity-averse nationalist Calvinball

That’s why I think that conservative white Americans find it so hard to accept that, say, academic American historians who tell unpleasant stories about our past are learned experts who tell it like it is in good faith. The identity-threatening dissonance is just too uncomfortable to sit with. So conservatives cope. The easiest way to cope with the story that credible American historians tend to tell is to outsource your expertise identification needs to conservative commentators (they’re expert experts!) who say that you shouldn’t trust them — who say that these out-of-touch woke egghead elites sneering down on all of us from their ivory towers are intentionally spreading misinformation because they hate America, want to tear down what makes it great, and replace it with something bad, foreign and dystopian, like …. I dunno, functional democratic institutions or an adequate social insurance state?

However, dismissing inconvenient truths by impugning the messenger doesn’t fully meet the challenge of keeping on the sunny side. It remains that America has a lot of profound problems that simply cannot be denied. So the next step is to blame all our undeniable problems on the evil and incompetence of your cultural/political rivals while pretending that the places where most Americans live don’t really count as part of the country. This leaves conservatives in a position where they can say that America is unambiguously great … except for all the ways in which the left and “elites” have turned it into a tyrannizing garbage fire.

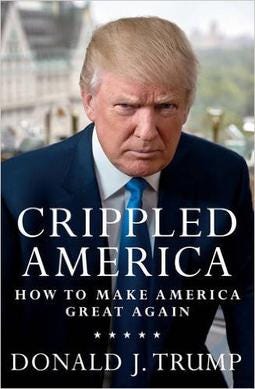

This is how you end up with the truly baffling Calvinball of conservative national assessment. America is the greatest country in the history of the world! It is also “not great,” “crippled,” and the victim of “carnage” roughly in proportion to the extent that Republicans don’t control things. A meaty majority of the American population dwells in large metro areas, which are all run by Democrats. These places are thus unmitigated disasters. You might think that an ambiguous “part good, part bad” mixed judgment of America’s merits would be logically inescapable once you’ve committed yourself to the idea that half the country lives in one or another crumbling, corrupt, crowded, crime-infested hellhole. Indeed, it is logically inescapable.

But this isn’t logic; this is a coping mechanism. That’s why the problems that beset America’s cities, whether real or imagined, don’t exactly count against America because they count first against Democrats and Democrats aren’t really American. Or maybe it’s that multicultural Democratic-majority cities don’t count as part of “real” America, so the horrendous problems they are imagined to have can’t drag down America’s greatness score. Either way.

At the end of all these intellectual and emotional gymnastics is relief. Really, there’s nothing to not be proud of. Because if American history makes you feel bad, it’s a lie. If the places where most Americans live are terrible it doesn’t count because those aren’t real American places that count. If there’s anything about our country that is seriously and undeniably bad, it’s because disloyal fake Americans are preventing us from being the greatest country on Earth by scandalously denying that we are.

Anti-wokeness is so defensively patriotic because “wokeness” isn’t just an illiberal crusade to abolish nature, persecute “normal” Americans for mind-crimes, and establish a tyrannical hierarchy of intersectional grievance. It’s the source of the internal treason that leads people to steal the historical spotlight from Betsy Ross and turn it on the sickening experience of enslaved people and hunted natives. Nobody who truly loves America would do that, because you can’t witness these scenes without a disloyal dissipation of the pride we’re right to be proud of. So that must be what the woke want in their relentless push to make us look. They hate America, hate our pride in it, and want us to hate it, too.

"...but because I’m a human who has, like every human, experienced first-hand how my mind generates resistance to information that threatens my political and cultural identity." This is fascinating to me because I'm a Chicana, brown mestiza and there's very little in American mass media culture that I don't find threatening to my political and cultural identity. I mean, the L.A. Times had to apologize for decades of racist coverage of Mexican-Americans in their newspaper, my family has lived in L.A. for over a century - we've had to live with that this entire time

Anyway, I digress. I guess what I'm trying to say is that I find this need to expunge discomfort and ambiguity is totally foreign to me. I'd have to go hide under a literal rock if I didn't want to feel discomfort or escape ambiguity. My very identity is rooted in ambiguity. Anyway, great piece! I enjoyed reading it.

It’s crazy how much this hits home. I was dubbed the “80 y/o conservative curmudgeon” by my high school social studies teacher for arguing with every “PC liberal” in class. Instead of the chief of police, my dad was a well respected (moderately conservative) banker in my southern MN town. Instead of majoring in philosophy, I chose its cousin, physics at a liberal arts college. I married an artist. I campaigned for Ron Paul and joined the LP briefly and voted for Mike Gravel for the 2008 nomination. I desperately wanted the world to make sense and libertarianism offered F = m*a simple logic that seemed indisputable. Then I took Quantum Mechanics and that only made sense if you could get a handle on free will and consciousness. So I studied neuroscience, and discovered how irrational our brains are. The rational economic libertarian actor was fundamentally flawed. It all started falling apart. The world is a messy place. I couldn’t deny the gray shades any longer.